A breakthrough

So I’ve made a bit of a breakthrough with this weird process of mine (and if you read my last post, my finger is now fine, albeit with a cool scar, thanks).

I’ve struggled for a couple of months with the seeming - and I’ll be honest, actual - randomness of this process.

If you’re not up to speed with what I’ve been doing, then I highly recommend catching up with these lovely blog articles here and here; but in short, I am breaking the digital stacking process in order to achieve images that speak to the archaeological thinking that I’ve been fascinated by for the last 3 or so years.

Each image that I make begins with a sort of dance with the camera around the subject. I move the camera in a specific way, making tens to hundreds of short exposures as I go. I want to make it clear; the end result is not a long exposure. It is the amalgamation of all of the short exposures I made as I moved around my subject.

In a small way, this was intended to be a homage to my old mentor, John Blakemore, who we lost earlier this year. His wind series was a sort of analog version of this, although he didn’t move around his subject in the same way. He allowed the wind to create the vital differences between each exposure. He also did this with analog tools which is, honestly, incredible.

In my case though, I’m breaking the digital stacking process that people traditionally use to create either noise-free astro images, or macro images that are in sharp focus from front to back.

Over the last few months I’ve been as frustrated by this process as I’ve been rewarded. It’s a laborious job that also takes a lot of processing time on my MacBook Pro. It’s an M3 Mac, so pretty powerful when it comes to image editing, yet it can take days to create something I’m happy with. A basic stack can take hours to begin with, exporting a final image takes even longer.

This is not helped by the size of each image in my stacks. From the beginning I’ve purposely gone out with my medium format Fuji GFX to make this work, even though the final results barely have any recognisable detail in them. So I have files which contain 80 to 150 stacked 100 megapixel images.

This is because:

1/ from the outset, I’ve known that I wanted to print these images upwards of 40x50 inches (possibly much larger) and even though they might not have recognisable detail in them, they do have detail, they do have resolution. This changes depending on how I stack them, but it is a real consideration.

2/ My focus on archaeological thinking means that I must have a consideration towards preservation of information. Each layer in my stack, I see as being analagous to a layer in an archaeological dig. Therefore I must preserve as much detail as possible in each layer. This then leads to images that speak to the archaeological process. They invite a sort of fuzzy interpretation of the evidence that mimics archaeological interpretation itself.

This process has been maddening. I’ve been trying to make images that look a particular way, achieved using a specific mathematical “median” function of the stacking process in Affinity Photo 2 (Adobe Photoshop does this too, but I’m moving away from them for ethical reasons). However it’s been difficult to guarantee that “look” despite trying to keep my variables as similar as possible. Sometimes I try the “mean” function and it looks much better, but the effect is different, and I’m still unsure that they can coexist in the same project.

This is the same stack. Median on the left, mean on the right.

Sometimes the geography is the issue. I simply can’t move the same way every time, because I’m restricted by the landscape, or fences, or something else. Sometimes it’s something more esoteric, like the relative size of my subject in the landscape, or the complexity of the sky. A nice blue sky with some fluffy clouds can be a nightmare for this process.

And given that I don’t find out until I’ve been working on the images at home for hours or days; well, the feedback loop is glacial. There’s no chimping here. I don’t know if I need to redo the shoot or if it’s a waste of time until much of that time has passed.

But a couple of weeks ago, I realised that some extra effort might solve this problem. I wondered if I could manually adjust each layer so that some were nearly aligned and others were completely misaligned, so I went out to a forest nearby with some pylons in it, and did my dance around them.

Initially, my results were disappointing, but then I went in and manually aligned every image so that one pylon in particular was overlapping itself in every layer.

This was not great, but I already knew that it wasn’t the final step. I went in and deliberately misaligned every second layer by hand. It started to break up, but not enough. So I went back and one by one misaligned the layers I hadn’t touched yet. Suddenly, with the misalignment of one last layer, it clicked. It instantly went from messy to a ghostly trace of something, and I knew I had something I could replicate.

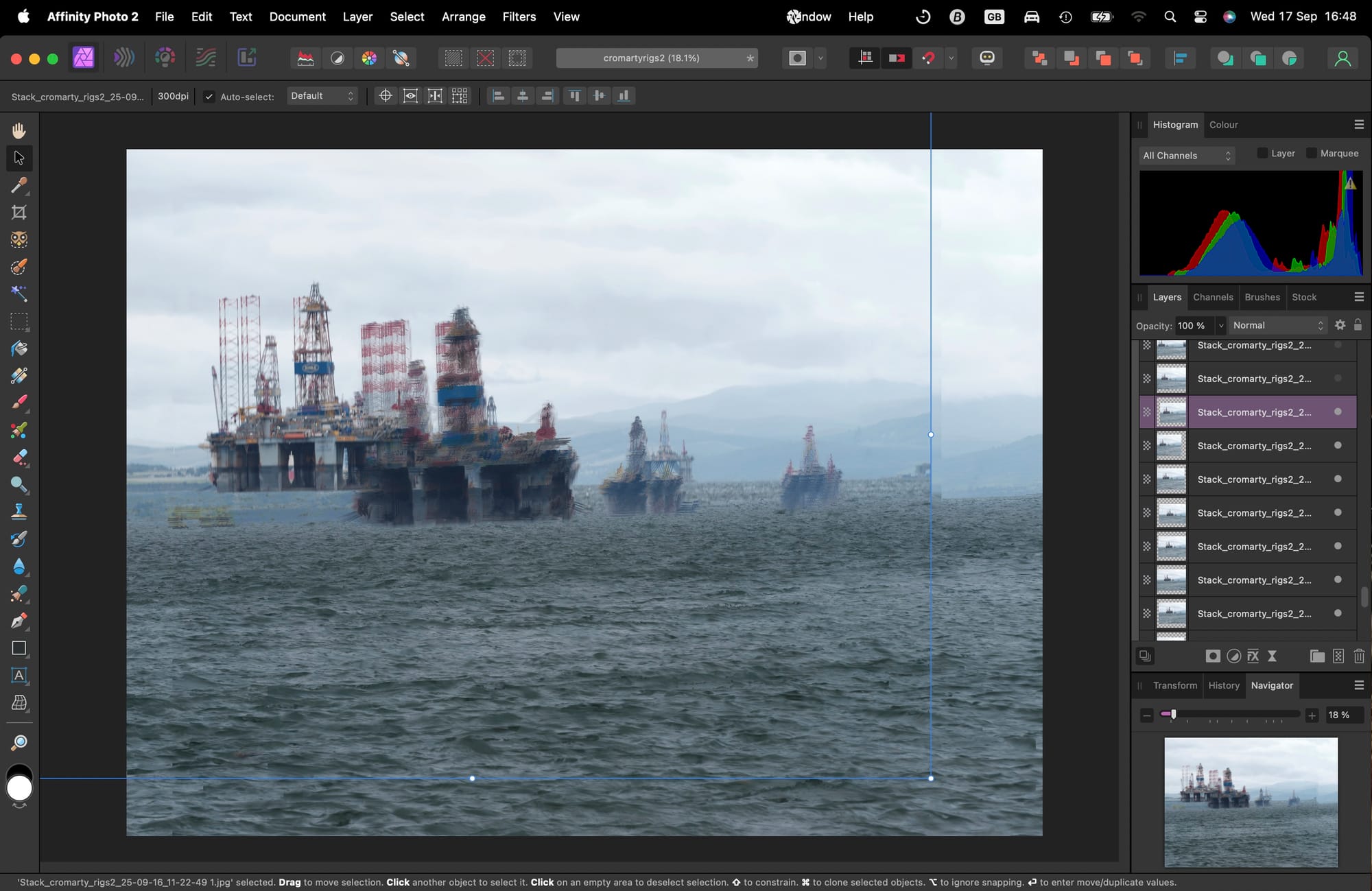

Last week I travelled to where I grew up in the Highlands of Scotland to photograph an oil rig graveyard in Cromarty. Armed with this new knowledge I had a lot more confidence in what I was producing than I’d ever had before, and after just a day’s work on the MacBook I’m seeing that this is now a reproducible process. It requires a lot more effort, but it’s much more reliable, if not predictable.

Stacks of images of various oil platforms. All of these are median, but the weather, relative colours, the background and the amount I was able to move all heavily influence the final results.

These images are not final images, but they show me that I can do this again, and again. With a few days work I think I can get something out of these images that will go in my final project. That’s a massive step forward.

The next step is one I’m sort of wary of taking. It’s occurred to me that because I can deliberately misalign these stacks after the fact, maybe I only need one image that is duplicated many times on - say - a hundred layers. Would I get the same effect? My guess is not quite, because I suspect the big factor in these images looking the way they do is not the subject, but the changes in the foreground and background.

But if it’s close enough to the effect I want, then perhaps I can turn my camera towards some more problematic subjects that I might only be able to get one image of. An industrial plant for example.

I’m nearing the end of the development/image-making phase now. I need to start thinking about research and writing; but there’s still some space in the calendar for making images that can fit into this project, so stay tuned for perhaps one more post on this process.

Then it’ll be down to the nitty gritty of the academic side of this final work.

![Direction[less?]](/content/images/size/w600/2025/07/colour_Jul-01-2025moveandstack4TBA-protected-intensity-DEFAULT-V2-1.jpg)