Direction[less?]

![Direction[less?]](/content/images/size/w1200/2025/07/colour_Jul-01-2025moveandstack4TBA-protected-intensity-DEFAULT-V2-1.jpg)

So, I should really start writing and talking about my current project, the FMP; the Final Major Project. It brings with it a fair bit of self-imposed pressure I have to admit, and my largest failing when under such pressure is this... I procrastinate.

Sure, I’m not the only one, but I feel like I have a particularly unique and honed talent for it.

Almost halfway in and I’m still experimenting. Absolutely, some of that is down to the weather, and the heat exacerbating my chronic health issues (the chronic in PhotoChronical) but some of it is down to what has become my perennial cry during this MA just after I’ve pitched my ideas.

“Oh my god. What have I done?”

I’ve pitched a decent idea, I think. I got a good mark for the pitch at least. Landscapes of the Endlings (working title, thankfully) - the last of our species. Imaginary and abstracted landscapes that try and peer into the fuzzy far future. Deep time inverted if you like.

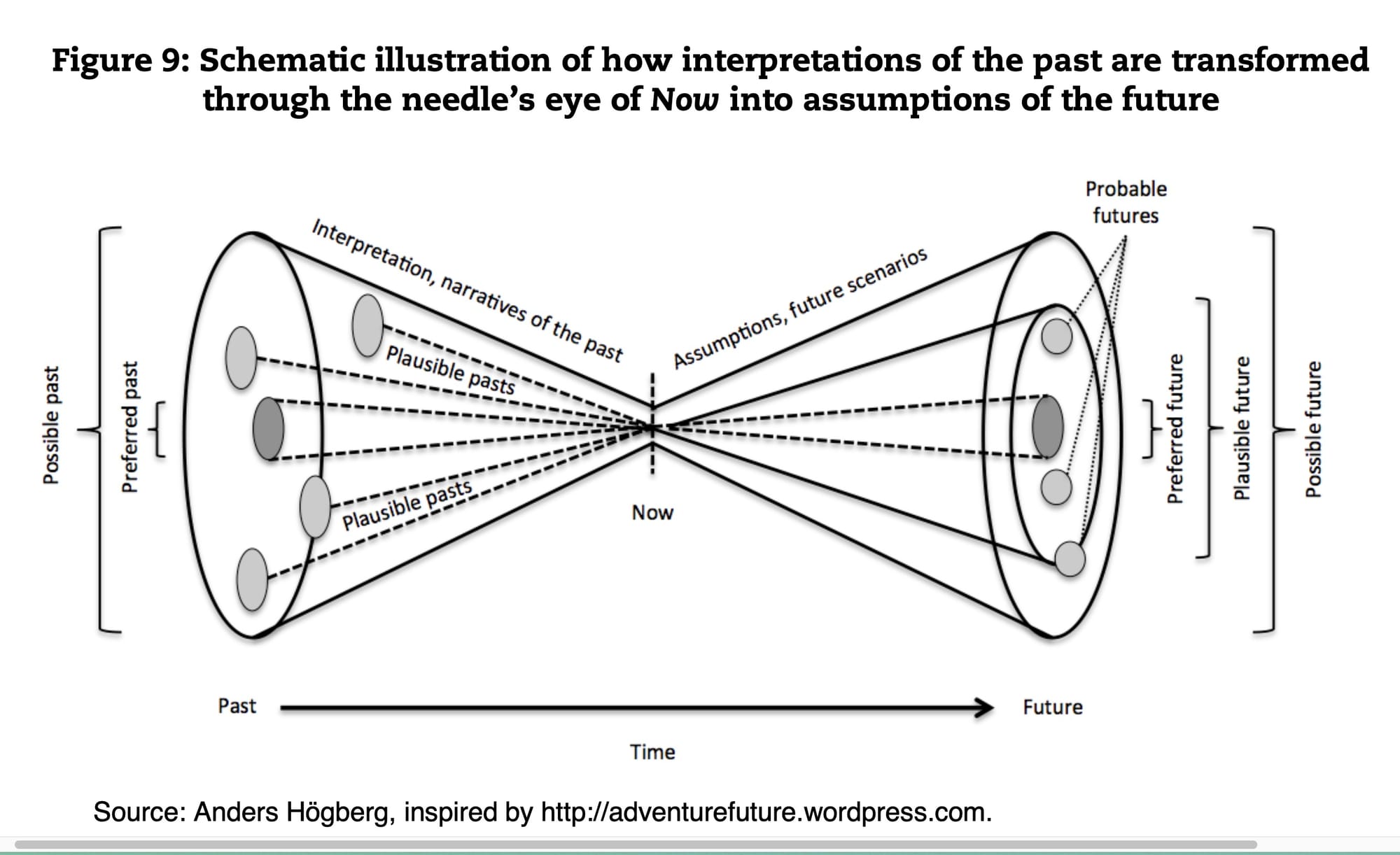

The diagram above helped me anchor the work, and gave me a way forward; a way to speak about it. I've used it before actually, in my previous project which I've yet to talk about on this blog (watch this space). It’s to be found on the International Atomic Energy Agency website in a paper by archaeologists who are concerned with the far future and how we keep humanity safe from the nuclear waste we have produced, given that it will remain dangerous for an unimaginable stretch of time into the future.

As Tim Morton, the philosopher, wrote:

“... think of [...] all the plutonium we’ve made, ever. That plutonium decays for 24,100 years before it’s totally safe. That’s an unimaginable time. I can just about wrap my head around 500 years when I think about Styrofoam. But 24,100 years? Yet I’m obliged to act with a view to the people, whoever they are, who are alive at that point. Who knows whether I would even recognise them as human?”

The diagram shows us “fuzzy futures” and “fuzzy pasts”. These probable, plausible and preferred pasts and futures; interpreted through the lens of the “now” by archaeologists - and I would argue artists like me who are concerned with contemporary and future archaeology in their work. It’s a short skip and a hop to begin thinking about future archaeology too.

That is, how will the things we leave behind be seen by those who come after? Will they blame us? Maybe they should.

As Robert MacFarlane writes in Underland:

“Perhaps above all the Anthropocene compels us to think forwards in deep time, and to weigh what we will leave behind, as the landscapes we are making now will sink into strata...”

My images, which (at least in this early experimental phase) are created from many tens to hundreds of images made as I dance the camera around the subject, are stacked. A laborious process which itself can be regarded as somewhat archaeology adjacent. The more layers you remove the closer to the factual location you get. They are also analogous to those numerous plausible and preferred futures in that first diagram. The further into the future you go, the fuzzier it will get as the possibilities expand.

I imagined, to begin with, that I was peering into the future to glimpse something of our fate. But now I wonder if these images are more from the point of view of someone in the deep future looking back, trying to imagine this world that caused it all.

I started with subjects that were contemporary archaeological “ruins”. A 150 year old winch, a barracks from the first world war that is disappearing into the forest. The important element is that there’s a trace of structure there. Something recognisably un-natural which, depending on how I stack these images, will come through in the final result.

I have found also, that it depends greatly on how I move. That first image, was very difficult to replicate and took me a few weeks to get a similar result. There is a dance in the successful images.

I’m still learning the steps.

Now though, I’m about to make things much more difficult for myself. If I do decide that this is from the perspective of our endlings peering back to the now and grasping only the fuzziest visions of it, then I need to turn my camera towards the things that will be to blame. The polluters, for example; the coal and nuclear power stations; the protagonists in the oil industry, the places where the rigs were built perhaps. Maybe some of the agents of hope too, wind farms spring to mind.

But these are difficult to photograph at the best of times, especially nuclear power stations. I might need a longer lens and be much further away. Which means the steps in my dance go from a couple of feet apart to perhaps 20, 30 or much more. I become more beholden to external factors and also, let’s face it, my ability to carry a camera a much longer distance. My body might have something to say here. These images I’ve posted here involved perhaps 15 minutes of movement each. A larger structure will take exponentially longer.

And then of course, there’s the little devil on my shoulder saying: “If it’s so abstracted, why go to the bother at all?”. Except that’s sort of the point, I think.

But, here comes Robert MacFarlane again:

“Beyond a hundred years even generating a basic scenario for individual life or society becomes difficult, let alone extending compassion across much greater reaches of time towards the unborn inhabitants of worlds-to-be...”

I think this is perhaps what I’m striving to do here. To imagine our descendants in deep time; and hold some compassion for them.

I’ve been given some great direction (and by this I mean more of a compass needle than being told “go there now”) by my tutors. I don’t feel this is a lost cause. But I don’t think I’ve ever felt quite so lost when I’ve simultaneously got a great idea of where I’m going.

The next couple of weeks will hopefully get me over the hump.

Fingers crossed.